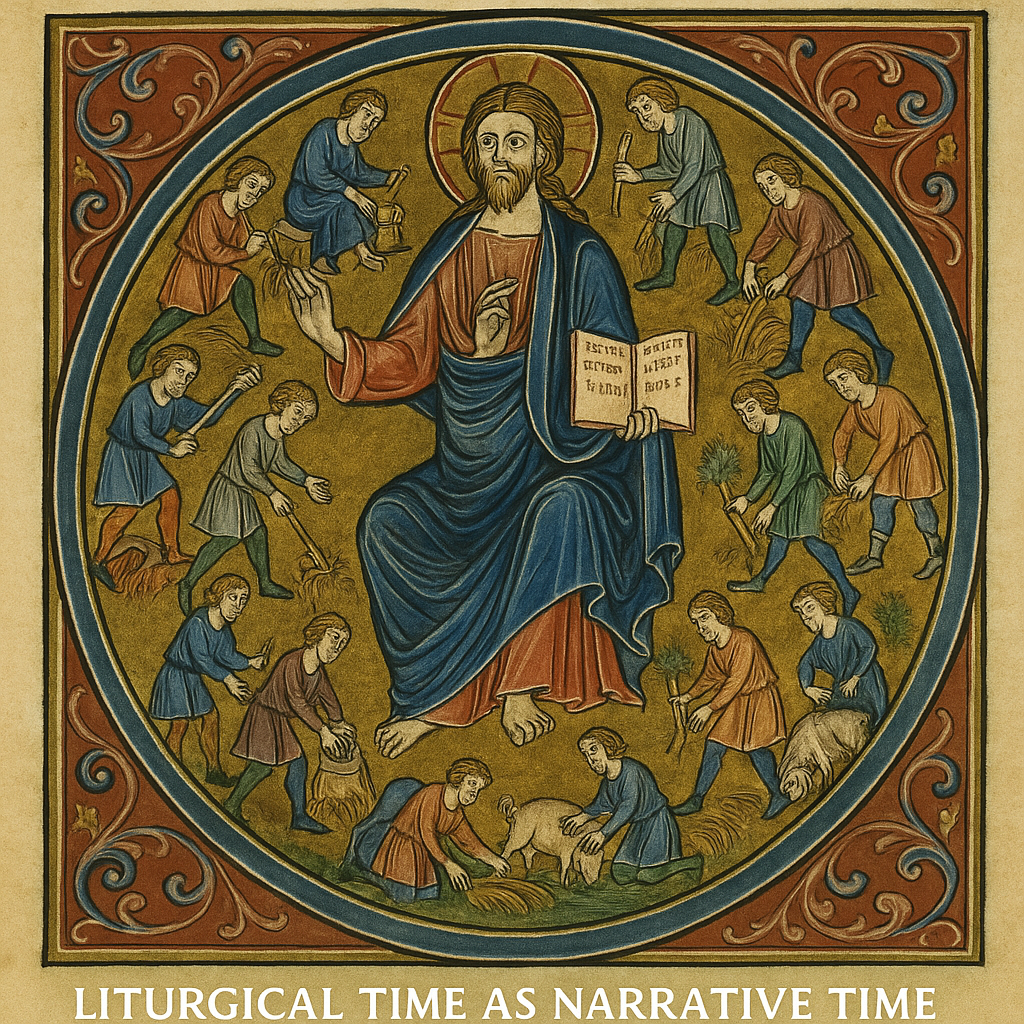

We tend to think of time as a straight march—beginning, middle, end. But in the Middle Ages, time moved in circles. Days were not counted only by sun and season but by the Church calendar: Advent, Lent, Easter, Pentecost, fast after fast, feast after feast. To live was to live inside liturgy. And if historical fiction wants to be true to that world, it must recover this rhythm.

Not Just Chronology

A medieval did not say “in March” without also saying “in Lent.” To march in August was to march under the shadow of the Assumption of Mary. A journey begun on September 29 carried the weight of Michaelmas, when angels were honored and rents were paid. Time itself carried meaning, and meaning shaped story.

This mattered because time was not abstract. It told you when to plant, when to fast, when to fight. A soldier could not separate his hunger from the season, nor a priest his prayers from the feast day. Characters breathed the liturgical calendar as much as they breathed air. If we write their lives without it, we cut them out of their own imagination.

Time as Weight

This rhythm altered pacing. Fasts slowed life down; feasts quickened it. The great seasons pressed down on daily life with their own gravity. A chapter set in Holy Week must feel taut, heavy with dread, silence, and betrayal. A Pentecost chapter must crackle with fire, whether of faith or of war. Even violence shifted with the calendar. Blood spilled on Corpus Christi was not the same as blood spilled on an ordinary Tuesday. Medieval people knew this. Writers should too.

And because the medieval world lived closer to hunger, fasting was not symbolic—it was physical. Forty days without meat in Lent meant lean bodies, weakened tempers, thin blood. Soldiers marched on empty stomachs. Priests muttered Mass with hunger in their bellies. Children cried through the night for lack of milk. The calendar slowed them down, literally. That must show up on the page.

How They Saw It

Medieval chronicles show it plainly. The Battle of Hastings came weeks after the Feast of St. Michael, patron of heavenly armies, giving the clash a cosmic frame. William the Conqueror was crowned on Christmas Day, binding his kingship to the Incarnation itself. Kings and bishops deliberately chose feast days for oaths, councils, and coronations because the liturgy gave events weight.

Disasters, too, were recorded this way. Famine years were marked by saints’ feasts: “On the day of St. Lawrence, hunger struck the land.” Plague deaths were written down with reference to Easter or All Saints. Memory itself was shaped by liturgical time. When men thought of their lives, they thought not in numbers but in feasts.

For the novelist, this means chronology alone is never enough. A date like “October 14, 1066” meant nothing to a villager. But “the weeks after Michaelmas” meant rent was due, harvest was ending, winter stores were uncertain. The calendar was not an accessory—it was the very structure of life.

Symbols in Season

The medieval imagination read seasons as signs. Lent was ash and hunger; Easter was new light. A siege dragging through Lent became an unchosen fast. A wedding on a Marian feast became a union cloaked in purity. A death on All Souls’ Day resounded with memory and prayer for the dead. Narratives bent because time itself bent.

Take harvest. Michaelmas was not just the end of a quarter year; it was the day of reckoning, when rents were paid, debts tallied, servants dismissed. A story set in September cannot ignore that. Or take midsummer: the Feast of St. John the Baptist carried its own fires, its own rituals of cleansing, its own sense of turning. Characters lived inside those signs whether they wanted to or not.

Even saints’ days mattered. Soldiers invoked St. George in England, St. Denis in France, St. Olaf in Scandinavia. They marched not on “April 23” but “St. George’s Day.” When they bled, they bled under the patronage of saints. That shaped how they saw themselves—and how we should write them.

The Writer’s Task

This is why liturgical time matters for historical fiction. It resists our modern instinct to drive forward endlessly. It circles back—feast to feast, fast to fast, penance to grace. It teaches recurrence, not just climax. Medieval life pulsed with this rhythm. And if we write without it, we’re not writing their world. We’re writing ours, dressed in borrowed clothes.

The novelist’s task is to let narrative time echo liturgical time. To let the year’s feasts and fasts shape not just the background but the pacing, the symbolism, the very texture of the story. If you want to write a novel set in the medieval world—or any pre-modern world—you cannot simply measure hours by the clock or dates by the calendar. You must let time breathe as they breathed it: sacramentally, seasonally, cyclically.

Only then does the story live. Only then does the fiction echo the truth of the past. Only then does the page keep time with the bells.